An organizational chart of Iran’s institutions looks like two complete systems, one democratic and another theocratic, mashed together.

Mohammad Ayatollahi Tabaar, a professor at Texas A&M University who studies Iranian politics, said that Mr. Khomeini and his allies hoped the two systems would clash.

Professor Tabaar called the theocratic institutions “a complete counter-state” that Mr. Khomeini and his allies “thought eventually would absorb the state.”

Mr. Khomeini seemed to anticipate a gradual takeover. He took office in the holy city of Qom rather than Tehran, the capital, and warned clerical leaders against sullying themselves with day-to-day politics.

But in 1980, just months after the new Constitution was approved, Saddam Hussein, the president of Iraq, invaded Iran.

The war, which lasted eight years, led Iranians to seek out a strong national leader. It also threatened to break the fractious new government.

Mr. Khomeini consolidated power for himself. His office, conceived of as a distant religious authority to be consulted only on certain matters, came to dominate the political system outright.

Factions Fighting for Dominance

When Mr. Khomeini died in 1989, a year after the war ended, it threw the system that had consolidated around him into doubt.

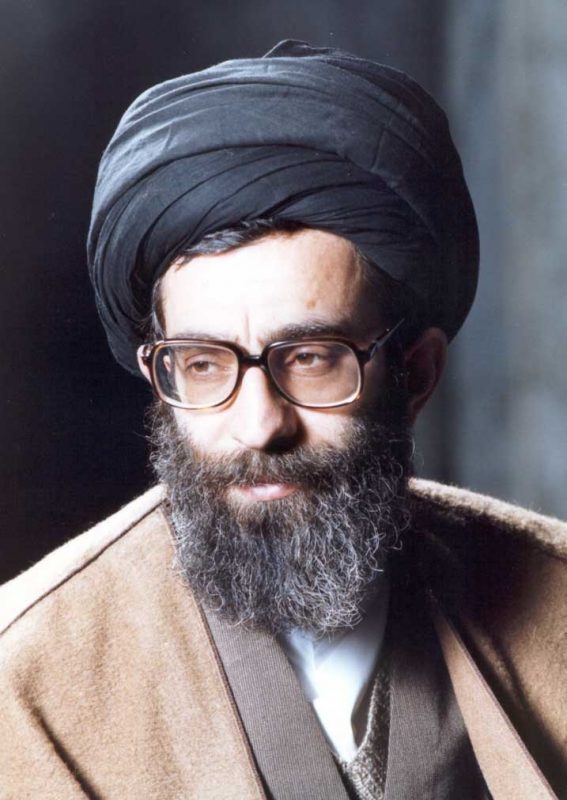

His allies feared that the office of supreme leader would be weakened with his death, shifting power to elected officials. They rushed through Ali Khamenei, who was then the president, to become the new supreme leader, an office he still holds.

But Mr. Khamenei lacked the necessary religious qualifications, so his allies pushed through a new Constitution to enable his ascent. This showed how politics were being waged among factions — ideological groups that lack the formal structure of political parties but compete just as fiercely. Ever since they have struggled to control the country’s unelected institutions, a fight often carried out in the shadows.

Mr. Khamenei’s allies, a faction is sometimes known as radicals or hard-liners, seized the supreme leadership to prevent losing it to another group, such as the reformists who favored easing hostilities with the West.

But Mr. Khamenei was far weaker than his predecessor. Unable to control the factions, he sought to manage them and at times swayed to their will.

Ever since, these factions have struggled against one another, at times in ways that alter the system itself.

In 1997, for instance, the reformist Mohammad Khatami won the presidency, despite efforts by Mr. Khamenei to shut down his campaign. Mr. Khatami replaced the heads of powerful security services, traditionally run by hard-liners, allowing him to ease political restrictions.

Hard-liners, concentrated in unelected bodies like the judiciary, fought back in ways that weakened democracy, such as shuttering newspapers or stifling demonstrations.

In 2000, after reformists swept the legislature, the unelected Expediency Council ruled that lawmakers could no longer investigate agencies that reported to the supreme leader.

During elections in 2004, Mr. Khamenei and his allies barred hundreds of reformist candidates, devastating their faction and returning power to his hard-liners.

This represented a period of consolidation for Mr. Khamenei, who also clashed with a powerful ally-turned-rival, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. Once a political kingmaker and a former president, Mr. Rafanjani was gradually sidelined as Mr. Khamenei strengthened his control.

Often, simple power politics, not ideological differences, drives these fights. Throughout 2011, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, though a hard-liner, clashed with the supreme leader as he sought to strengthen the presidency.

Do Iran’s Elections Matter?

The country’s elections may be just another venue in which factions can compete. But they can still give citizens a voice, albeit one much weaker than in full democracies.

“These are real elections with real political actors and real campaigning,” Professor Tabaar said. Their scope, however, is sharply limited by the Guardian Council, which is considered to be aligned with Mr. Khamenei, blocking all candidates who stray too far from the council’s preferences.

The system relies on elections that will be too restrictive to risk substantial change but open enough that Iranians, who expect a say, will accept their government as legitimate.

That would be difficult enough even if it were set out in the law. But because it is a matter of tacit understanding, reached between disparate institutions that do not agree on the optimal level of democracy, in practice, it can bring severe instability.

Mr. Khatami’s election, for instance, was followed by years of chaotic infighting. In 2009, when Mr. Ahmadinejad won re-election amid accusations of fraud, widespread protests briefly threatened to bring down the government.

Four years later, the system functioned more as intended. Hassan Rouhani, a moderate who was promising change but not so much as to provoke the system’s wrath, won the presidency.

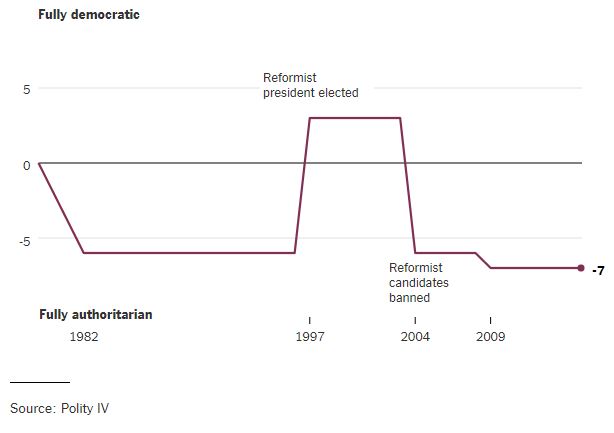

Rating Iran’s Democracy

To some, Mr. Rouhani’s election in 2013 was the system at its most democratic. He appeared to enjoy widespread popular support and has brought significant changes, like a diplomatic agreement to curtail Iran’s nuclear program.

Though hard-liners opposed these changes and Mr. Khamenei also expressed skepticism (as well as appearing to favor another candidate in the race), they bent to the public will.

To others, Mr. Rouhani’s tenure has been a reminder that Iran’s democracy is, at best, managed. By barring reformists, Mr. Khamenei funneled public demand for change into a more acceptable candidate.

Mr. Rouhani has been allowed to enact some changes but blocked from others. He often clashes with hard-liners, most recently accusing the Revolutionary Guards of seeking to sabotage the nuclear agreement.

Democracy is difficult to measure, but few metrics rate Iran highly. One, known as Polity IV, uses a number of indicators to rate countries from -10 for a full dictatorship to 10 for full democracy. It scores Iran as -7, the same as Cuba and China.